30 June 1924, like 30 June 2025, was a Monday. Different dramas played out in different parts of the world that day. In South Africa, JBM Hertzog became Prime Minister, a position he would hold until 1939 when he would be forced out of office over his insistence on neutrality in World War II, subsequently espousing National Socialism. At Lord’s England’s cricketers scored 503 runs against South Africa in a single day. In the US, 16-year-old Calvin Coolidge Jr, son of the 30th US president, played tennis without his socks, developing a blister which would become infected and kill him a few days later. Heart-broken Coolidge would not contest the following election.

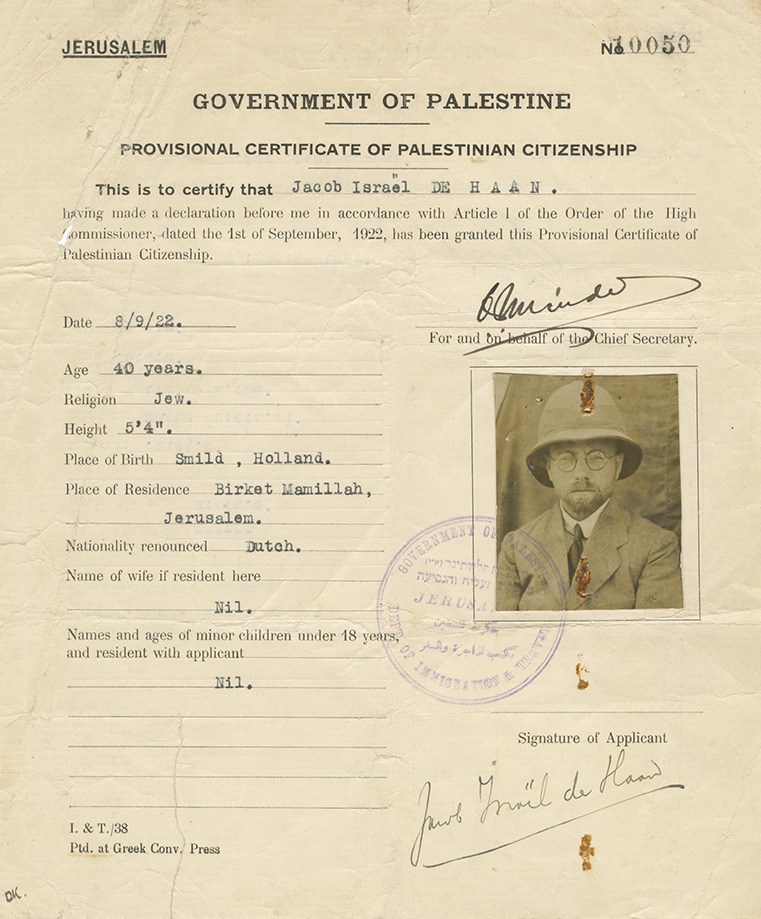

Jacob Israël de Haan knew none of this when he prepared to leave the synagogue at Sha’arei Tzedek in Jerusalem shortly after concluding his prayers with a recitation of the kaddish for his father who had died a month earlier. Perhaps he was preoccupied with his planned trip to London the following day with a delegation of orthodox Jews to plead with the colonial authorities against the Zionist plans for the Jewish community in Palestine. But de Haan would never leave Jerusalem.

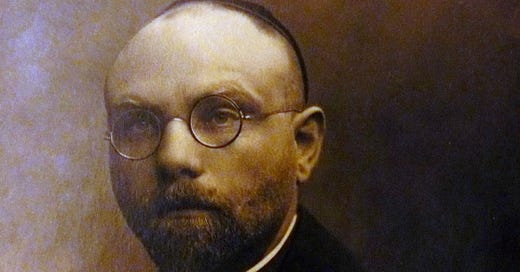

It is ironic that one of Zionism’s greatest threats arrived in Palestine as a Zionist. But ironies and contradictions seem to have defined de Haan’s short life. The Dutchman was an icon of gay pride, a seminal poet, a lawyer, a journalist, and a Jewish political activist, who traded the excitement of urbane bohemian life in Europe for a journey of self-discovery to Palestine.

De Haan’s arrival in Palestine was the culmination of a personal religious national awakening that began a few years earlier, as he was drawn to religious Zionism – a small and marginal trend that would have uncomfortable existence trying to bridge traditional religiosity with the radical secularism of the Zionist movement. Zionism was a secular movement that emerged as a fundamental rejection of traditional diasporic Judaism and sought to reinvent Jews as a race or ethnicity, and as a nation.

When he arrived in Palestine in 1919, de Haan immediately launched himself into the Zionist cause with gusto, at one stage defending Vladimir Jabotinsky and some other Jewish militants at a Jaffa court after they were charged over violent attacks on Arabs. He and Jabotinsky were among the founders of a law school, instituted by the British who needed jurists who could navigate the mixture of Ottoman, British and international law that prevailed in Mandatory Palestine.

But life in Palestine changed de Haan’s perspective, and the big transformation happened when de Haan was drawn in by the charismatic Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, the leader of the Haredi Jewish community in Jerusalem. De Haan became an ardent critic of Zionism. He rejected their secularism and decried their anti-Arab racism, the economic marginalisation of Arabs and the Zionist moves to exclude Arabs from Jewish-controlled spaces.

Being a journalist with a high profile in Europe, and being a highly educated legist, who apparently had a knack for languages and spoke English, Hebrew and Arabic quite well, de Haan came to function as the foreign minister and main international advocate for the anti-Zionist cause of the Haredi community in Palestine.

De Haan met with leaders and dignitaries in Palestine. He met with Hashemite royalty in Jordan. He became a correspondent for a leading British newspaper as well. And he used his legal skills, complete with courtroom antics, to frustrate the Zionist cause.

The Zionist leadership was alarmed by the prospects of an organic anti-Zionist Jewish presence in Palestine, one that was articulate, engaged with Western media, integrated into the local society and vehemently opposed to Zionist colonisation. The Zionist leadership mobilised its well-organised followers. Many tactics that were used then would play themselves again in the future.

The Zionist leadership moved to marginalise and isolate de Haan. His Zionist law students refused to attend his classes. He was boycotted. Zionist lobbyists put pressure on the Mandatory authorities to have him sacked from his academic position. He eventually was. And Zionist media and the Zionist rumour mill spread all kinds of stories including the inevitable allusion to gay sex, and sex with Arab men – each of which was unforgiveable in its own right.

A Dutch tourist who once accompanied de Haan through the streets of Jerusalem noted that some Jews they encountered along the way would spit on the street as they passed. The tourist commented on the disrespect, to which de Haan responded, "Oh no, they spit on the street out of respect for you, your presence. Otherwise they would have spat in my face."

And then there were the death threats. There were a few of those. In 1923 he received a message assuring him he would die by 24 May. This led to an article entitled “25” which he wrote on 25 May and began with “How silly is the 25th, when one is not murdered on the 24th."

While unexpected, it should have come as no surprise, then, when on 30 June 1924, 101 years ago today, de Haan would be ambushed and gunned down outside a place of worship – shot three times by Avraham Tehomi, a member of the newly formed Jewish vigilante militia, the Haganah. The assassination, masterminded and ordered by Yitzhak Ben Zvi, later Israel’s second president, stunned the deeply fractured British colony and Jewish communities within it.

Jerusalem’s Arab mayor, Musa Kazim Pasha al-Husayni, condemned the murder and hailed the victim. The Zionist media was jubilant. Haaretz could not contain itself, celebrating the departure of the talented-yet-evil man and his nefarious actions that threatened the Jewish Yishuv. The Zionist Organization’s weekly even delved into Jewish tradition for a long-standing rabbinic permission to kill traitors and collaborators at times of great stress.

In typical fashion the Zionist leadership itself remained tight lipped on the assassination and sought to lay the blame with Arabs. It would take decades – long after the creation of Israel – for the details of the assassination to be made public.

The assassination turned out to be a stunning operational and strategic success. With the elimination of de Haan, a vocal Jewish opposition to Zionism – one that held sway in British, European and Arab circles – was silenced. The Haredi community in Palestine was sidelined and had little influence over the emerging realities in Palestine, evolving into an inward-looking, aloof anachronism.

Jews who collaborated with Arabs got a vivid sense of what was in store for them. Zionist terror became a reality. Quite a few Jews would be executed for real or imagined collaboration with enemies in the years to follow. There would be no place and no mercy for the enemies within.

The ironies surrounding de Haan’s life continued after his death. In 1931, Tehomi and other militants would break away from the Haganah and form a new organisation that would become known as the National Military Organisation – Irgun Zva’i Le’umi – or the Irgun. That organisation was quick to align with the right-wing Revisionist trend of Zionism, installing Jabotinsky as its Supreme Leader – the same Jabotinsky, incidentally, whom de Haan had defended in a Jaffa courtroom only a decade earlier.

In 1937 the breakaway militia split. Tehomi and some others returned to the Haganah. But Tehomi never settled back into the organisation, and eventually moved on, emigrating in 1945 to the US to deal in precious stones, returning to Israel in 1968 to open a business in East Jerusalem, only to fall into debt and abscond from the independent Jewish state back to British territory, this time British Hong Kong, where he died, unrepentant, in 1991.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, Zionist narratives remain largely quiet about the story of de Haan’s assassination. The existence of anti-Zionist Jews, and anti-Jewish violence by Zionists do not quite fit the dogma.

But the story contains several other disturbing truths. One is the cult-like control that the Zionist leadership at the time, and since, would exercise over its followers, using mechanisms like social isolation, control of public discourse, and brute force to secure compliance. The other is how effective these strategies are. You can’t argue with the man with the gun. And you can’t argue with success. Zionism has both.

That was genuinely enlightening Allon

I have yet to read anything of yours that isn’t replete with fascinating and important information, not to mention brilliantly written. I’m sincerely grateful for your knowledge and your willingness to share it.